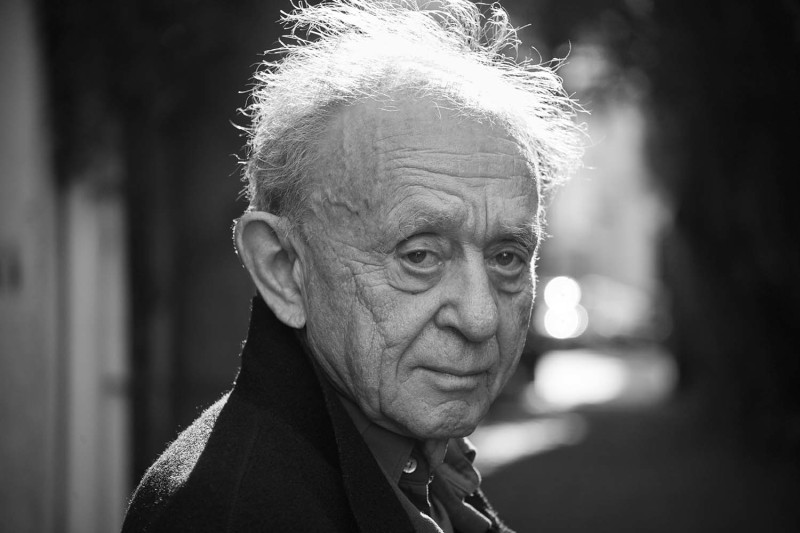

Text by: Luigi Locatelli, scholar and film critic

Translated by: Steve Piccolo

A legend of documentary filmmaking, at the age of 87 Frederick Wiseman competes for the Leone. After Berkeley and the National Gallery in London, with EX LIBRIS he shows us another cultural institution, the New York Public Library. A by-now labyrinthine and tentacular colossus that is difficult to convey for the director. We see it all – encounters with authors, training courses, digitalization programs, multiplying and spreading – but we never see a book. Never a reading room. Quite a paradox for a documentary about a library.

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury of Venezia 74 (names at this link), please consider well when you decide on the winner of the Leone d’Oro. If you must assign it to a legend, to a name above any suspicion and any possible rebuttal, give it to Frederick Wiseman, instead of Ai Weiwei. Je vous en prie. At the age of 87, and from the heights of a formidable filmography in terms of both quantity and quality, Wiseman continues to tirelessly turn out his documentaries, and to teach lessons in filmmaking to the whole world. This EX LIBRIS (yes, in capital letters) is not his best film, not quite on target, not right on focus, plagued by a surplus of ideological and political correctness unusual even for a director like Wiseman who has always been transparently liberal in faith and in practice. But it is still fully one of his films, not a betrayal of his past. Awaiting the verdict of the jury on Saturday, let’s talk about EX LIBRIS, an exploration in the Wiseman style (no interviews, almost zero captions, no explanations, just images that speak and tell the story) of the New York Public Library, a glorious American institution, a colossal machine that has produced culture and literacy (now digital) of the masses for over a century, with a special focus on the underprivileged. One of those institutions founded at the end of the 1800s by philanthropists driven by humanitarian intentions, aimed at improving the condition of the poor and the downtrodden, born and still private in spite of the word “public” in its name, still supported today above all by donations and only in part by public funding (mostly municipal). The central, historic facility on 5th Avenue is joined by 92 branches in Manhattan, the Bronx and Staten Island. A giant. Also a labyrinth that is far from easy to navigate and decipher, unlike other institutions already narrated by Wiseman, like Berkeley and the National Gallery in London. Unfortunately one doesn’t really understand what the NYPL is, from the film, and what its true mission is today. Everything is very vivid, as always in Wiseman, who is able like no one else to convey the immediacy of the living, doing and actions of people, whether or not they are important. He makes us feel interested in even the most humble existences, connecting them in a web of relations, a community, a whole. But at times the identity of the NYPL seems elusive, with all the tentacles it has today, operating on an infinity of different fronts. Too many, perhaps. What surprised me – not so pleasantly – was the fact that in this film everything is shown – encounters between authors and the public, training courses, digital literacy programs (seen as having a crucial, strategic role by the management), pre-school and after-school programs for kids, recruiting for the unemployed, iconographic consulting and all kinds of other situations – everything except books. You remember those things? Like blocks of paper with a cover. Well, in this library we can see very few books, even no books at all. Wiseman, for some strange reason I find hard to fathom, has shot and edited a film of three hours and twenty minutes on a glorious public library, one of the largest and best in the world, without ever – I mean ever – showing us a reading room. Or a library containing books printed on paper. There are computers everywhere, with throngs of people clicking and typing. But there is not one moment in which you see someone taking out a book on loan or returning one, someone asking for advice about a particular text. Or leafing through a book with curiosity. Or lost in the reading of a page or two. The rooms we see are mostly invaded by various electronic devices, and much emphasis is placed on the need for NYPL to make a contribution to close the digital divide, which means that in the city one out of three inhabitants is without an Internet connection in the home (we’re talking about New York, not Dhaka or Dar es Salaam).

Very well, good for you, let’s close the digital divide, but what about books? I mean the ones printed on paper? How commendable of the NYPL to give single mothers in disadvantaged neighborhoods kits for six months of free web access… but couldn’t they also suggest Joyce, or Kafka once in a while? You might reply: but Mr. Wiseman, the absolute legend of documentary filmmaking, is probably above and beyond the banality of showing us books in a library. He goes beyond that, to explore the less obvious, more surprising aspects, the social mission of the institution to raise the masses out of their ignorance. You might be right. But I still have the conventional idea that a library is a library is a library. A distributor of books, first and foremost. Period. Then, of course, Wiseman shows us all kinds of other lovely things. Like the authors who present (and promote) their own works, entertaining the audience, starting with Richard Dawkins, the English scientist who urges a militant atheism, which is not such a good beginning, actually. Dawkins, the author about 20 years ago of a brilliant, fundamental work like The Selfish Gene, now rants against the sacred and religion without any very subtle reasoning, and one doesn’t feel an uncontrollable urge to keep on listening. Among the guests of the NYPC we also see Elvis Costello (now and always against Mrs. Thatcher: “I’ll dance on her grave,” he sings) and Patti Smith. The film devotes an amazing amount of time to the admittedly hot topic of black Americans, and while I understand its crucial importance, I find it hard to understand certain ideological drifts documented by Wiseman. We see the young author of a book in which he claims that abolitionism (of slavery) was not, as the West has always narrated, the result of humanism or an enlightened culture of human rights that blossomed in Europe and America, but was a movement with solid roots in other cultures as well, including Islam, for example. While he is undoubtedly correct in saying that the Koran contains not one word that can legitimize slavery, he should be reminded that there were many Muslim Arabs among the biggest slave traders. Or elsewhere: we see a lecture on the first black American poetess (late 1700s), in an encounter with neighborhood mothers at a branch of NYPL, and hear complaints against textbooks that still smooth over and water down the scandal of slavery, implying the need for “other books that are respectful of minorities.” I could go on and on. There are other moments and other stories that bring some balance to this ideological overload, but the impression that the film is forcefully skewed still remains. Agreed, the NYPL was founded in its day with a clear humanitarian mission of social and cultural emancipation, and today we can only commend the fact that it continues to forcefully pursue that vocation. But I still can’t for the life of me help thinking that Wiseman could also have shown us one of those lovely reading rooms with counters polished by years and years of use, beautiful lamps, wood panels on the walls, relaxing shadows, with people quietly absorbed in reading to their hearts’ content.

Read the Italian version on Luigi Locatelli’s website