Text by Riccardo Slavik

We are the Stonewall Girls

We wear our hair in curls

We wear no underwear

We show our pubic hairs

The defiantly campy chant used to stymie the police during the Stonewall riots is one of many examples of camp and play being at the core of the Gay Liberation Movement since its genesis. Even at one of its most tragic and rebellious times, during the 80’s AIDS crisis, elements of clowning and camp, theatre and play, were often part of the protests staged by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP. ‘Clowning’ could run a varied specter of incarnations, from campy get-ups to drag, humorous chants to actual clown costumes as means of protest against the ‘clowns’ in power who were at the time hell bent on denying the very existence of an health crisis. Clowning, literal or otherwise, was for example a big part of the Stop The Church action in 1989, a protest against cardinal O’Connor and the catholic church’s stance on abortion and sex education. The spirit of the clown offers another way of being in the world. As clowns are not afraid of being seen as foolish, clowning offers a route toward openly questioning conventional ways of seeing the world. ACT UP member Ann Northrop has suggested that despite a lack of funds or access, much of their success was determined by a willingness to sustain public humiliation through a series of very public performances which transformed the way AIDS policy was conceptualized.

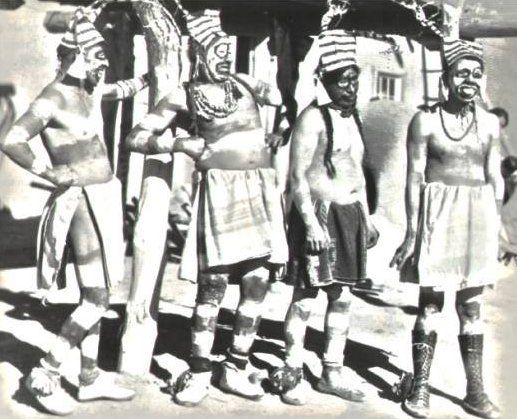

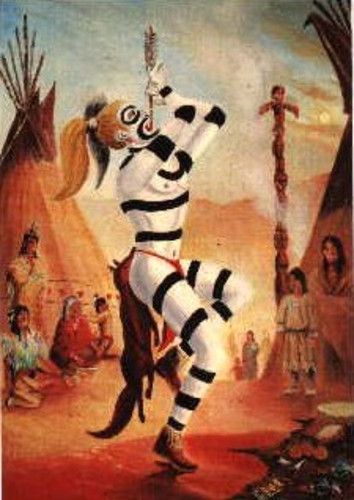

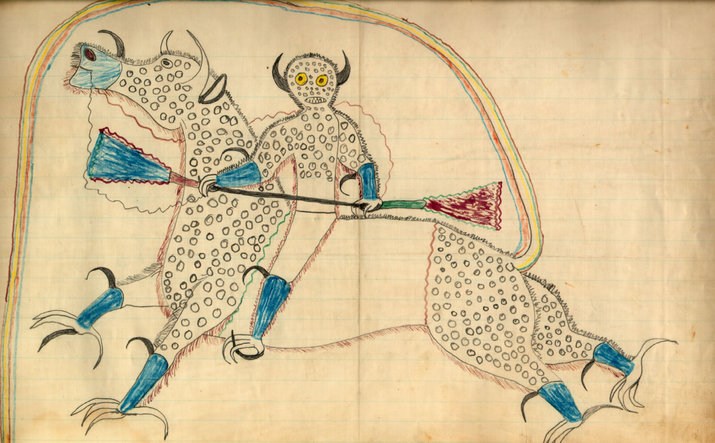

‘There is an old native North American Indian tradition called Heyoehkah. The Heyoehkas, or sacred clowns, were people within the tribe who ‘ did things differently’, challenged people’s thinking, shook them up. Their function was to keep their people from getting stuck in rigid ways of thinking and living. They were also known as ‘contraries’ because they lived backwards. They walked backward, danced backward, everything they did was contrary to the norm.

For gay people the role of the sacred clown is especially important: not only are the sacred clowns often gay, the role of contrary is a sacred symbol of the role we play in society as a whole.

There has been a sacred clown response to AIDS. When the normal response was to react with fear and panic, there were people dancing backward, responding with love and confidence. ‘( Tilleraas, P. 1988. Color of light: Daily Meditations for All Us Living with AIDS)

Dario Fo once wrote, ‘ clowns always speak of the same thing, they speak of hunger; hunger for food, hunger for sex, but also hunger for dignity, hunger for identity, hunger for power. In fact, they introduce questions about who commands, who protests’’ The clowns of the AIDS crisis, a crisis which, we must add, is far from over, are therefore both healers and rebels, they protest with humour while pushing a very serious agenda, they disconcert the authorities with their looks and antics yet manage to subvert the status quo. At a time when the LGBT movement faces internal struggles and external attacks, when so-called ‘allies’ and even members of the community think that drag queens and outrageous costumes shouldn’t be part of a political struggle, we must remember that the drag queens ARE the sacred clowns, our own Heyoehkahs, they provoke laughter in distressing situations of despair and provoke fear and chaos when people feel complacent and overly secure; their own existence is political and ‘queer’. As anarchists said in the tumultuous 70s: ‘Fantasy will destroy power and laughter will bury you”.