by Riccardo Slavik

“Nothing was holy to us. Our movement was neither mystical, communistic nor anarchistic. All of these movements had some sort of program, but ours was completedy nihilistic. We spat on everything, including ourselves. Our symbol was nothingness, a vacuum, a void.”(Georg Grosz on Dada)

“ I did not see myself as a fashion designer but as someone who wished to confront the rotten status quo through the way I dressed and dressed others. The way I thought about ‘punk‘ politics was this: …the world is appalling. It’s cruel and corrupt and dangerous and there are awful people running the world…And so first of all, punk was about contempt. Contempt for the older generations because they hadn’t tried to do anything” Vivienne Westwood

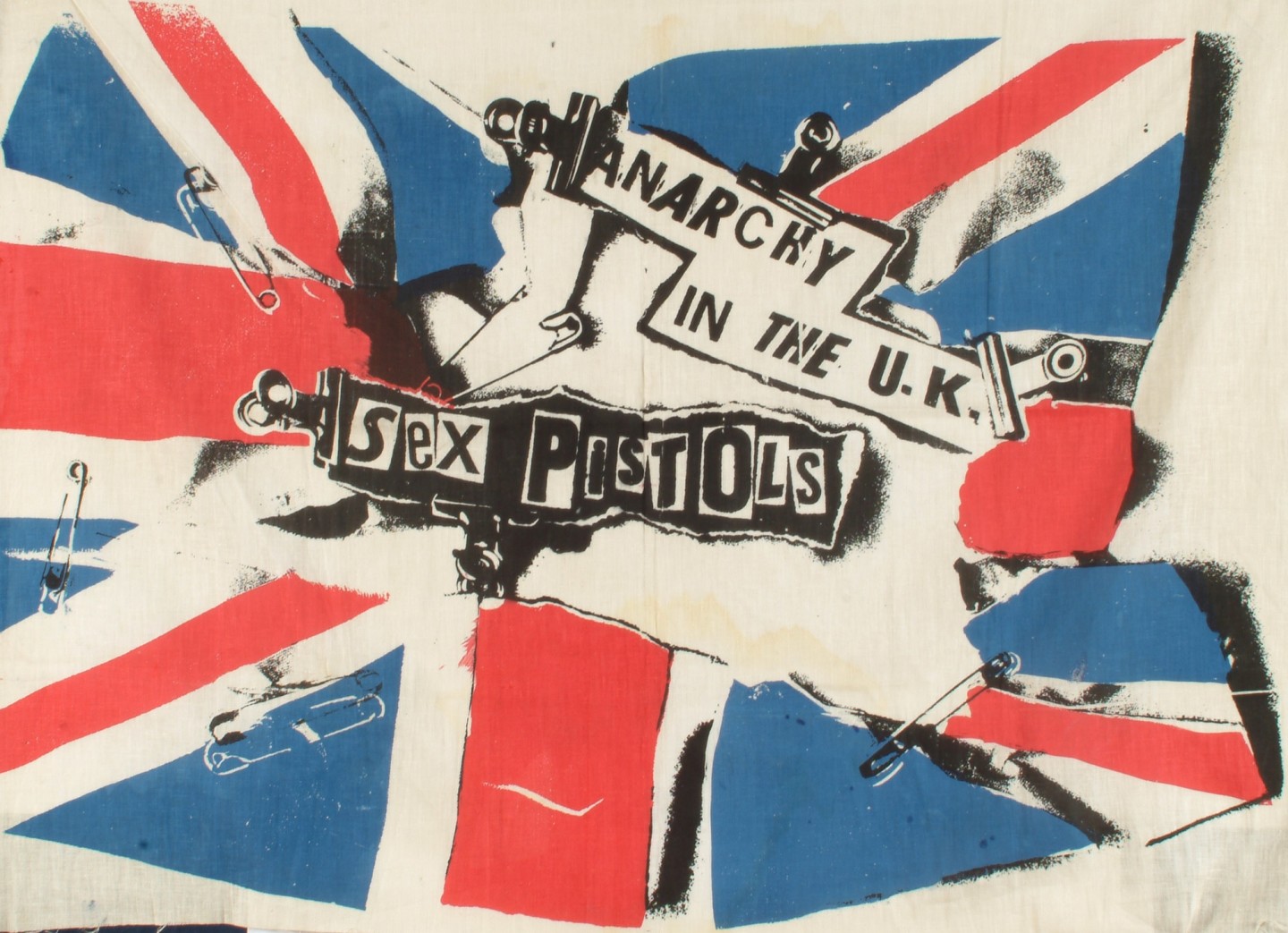

40 years on, the iconic power of punk is still palpable, and due to its unusual origins as a spectacular subculture, will probably remain unique. In sociological studies, subcultures represent ‘noise’, interference, in the orderly semiotic discourse of society and the status quo. The ‘spectacular subculture’ violates the authorized codes through which the social world is organized. Punk was probably the most spectacular of subcultures, even more so because, unlike most others, it sprung from an interest in revolutionary intellectual ideas like Situationism, and artistic currents like Dada and Surrealism. Their radical aesthetic practices – dream work, collage, ‘ready mades’ etc are certainly relevant here. They are the classic modes of anarchic discourse. Lettrism, applied to the simple t-shirt, the perfect working class canvas, became a tool for shock and confrontational politics.

England in the early 70’s was undeniably ripe for revolt, while, at the same time, in the U.S. a new musical style was quickly spreading, a faster, rawer form of rock’n’roll, a rejection of hippie exoticism and classic stadium rock; so it’s safe to say that some incarnation of ‘punk’ would have probably surfaced at some point. What made Punk the instantly recognizable bricolage of visual codes and an apparently insuppressible Subculture, was a little shop at 430 Kings Road in London.

“There was no punk before me and Malcolm. And the other thing you should know about punk too: it was a total blast” Vivienne Westwood

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood turned their little shop (in its various incarnations as Let It Rock, Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die, Sex, Seditionaries), in a haven for outcasts, a laboratory of social revolt and a playground for art-school experiments, through their fascination with subcultures and teenage rebellion. The building blocks of this cut-up of ultimate chaos were Teddy Boys, Rockers, Anarchists, Situationists, and the most explosive of elements: Sex. As Vivienne says, they were so fascinated with cults and subcultures “We invented one of our own. It wasn’t invented from the streets, it was the other way around”. And therein lies the power of the punk image, a bricolage of ‘semiotic guerilla warfare’ (Eco, 1972), it was born in a singular space and time and used easily accessible codes which could then be reproduced, copied, spread like a wild-fire through cities and nations once the look and the sound finally came so famously together. Of course punk did more than upset the wardrobe, it undermined every relevant discourse, the cacophony of anarchic pop that was McLaren’s idea of the Sex Pistols was the perfect sonic commentary to this spectacular subculture. As Dick Hebdige brilliantly writes (in ‘Subculture; the meaning of style’ 1979) :’’Clothed in chaos, they produced Noise in the calmly orchestrated Crisis of everyday life in the late 1970s- a noise which made (no)sense in exactly the same way and to exactly the same extent as a piece of avant-garde music.’’

Vivienne Westwood famously said that what they were doing was “making clothes for heroes and encouraging sedition- seducing into revolt”, and this nihilistic heroism, having no real goal other than Chaos, and effectively embracing failure and negative reactions, could paradoxically be invincible and beyond criticism. The term ‘punk’ itself, born as an insult, was turned around and embraced to spite a society that felt unjust and uncaring. Punk started in the art-school crowd, with ideas taken from Debord and Dada, but spread to all levels of angsty youth because it embraced the Cheap, the Nasty, the Degraded.

“Punk style was defined principally through the violence of its ‘cut-ups’, the most unremarkable and inappropriate items- a pin, a plastic clothes peg, a television component, a razor blade, a tampon- could be brought within the province of punk (un)fashion. Anything within or without reason could be turned into part of what Vivienne Westwood called ‘confrontation dressing’ so long as the rapture between ‘natural’ and constructed context was clearly visible. Objects borrowed from the most sordid of contexts found a place in the punks’ ensembles… turned into clothes which offered a commentary on notions of modernity and taste. “ Dick Hebdige (1979)

All Photographs from the book “Punk London 1977” by Derek Ridgers